Here is an article by C.S. Lewis entitled A Dream where he describes the eternal revocation of our rights through emergency powers enacted by Local/Federal Government cretins.

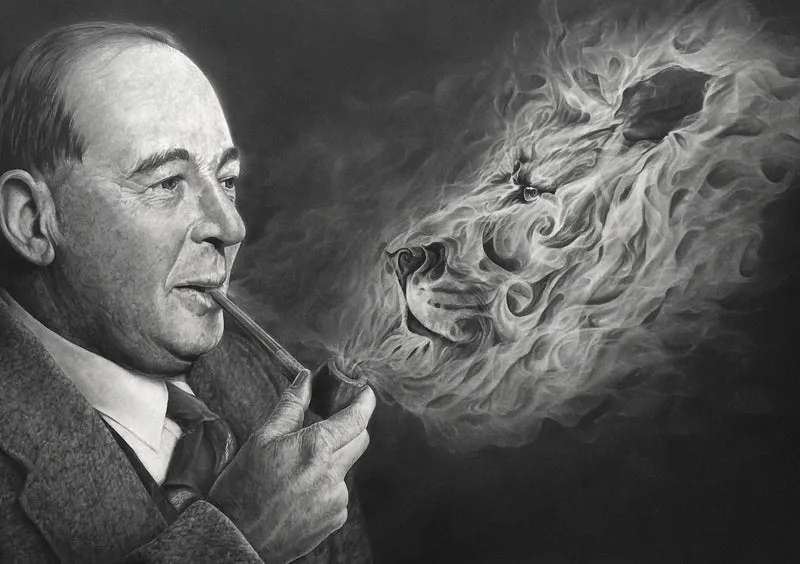

A Dream by C.S. Lewis

I still think (with all respect to the Freudians) that it was the concourse of irritations during the day which was responsible for my dream.

The day had begun badly with a letter from L. about his married sister. L.’s sister is going to have a baby in a few months; her first, and that at an age which causes some anxiety. And according to L. the state of the law – if “law” is still the right word for it – is that his sister can get some domestic help only if she takes a job. She may try to nurse and care for her child provided she shoulders a burden of housework which will prevent her from doing so or kill her in the doing: or alternatively, she can get some help with the housework provided she herself takes a job which forces her to neglect the child.

I sat down to write a letter to L. I pointed out to him that of course his sister’s case was very bad, but what could he expect? We were in the midst of a life and death struggle. The women who might have helped his sister had all been diverted to even more necessary work. I had just got thus far when the noise outside my window became so loud that I jumped up to see what it was.

It was the W.A.A.F. (Women’s Auxiliary Air Force) It was the W.A.A.F., not using typewriters, nor mops, nor buckets, nor saucepans, nor pot-brushes, but holding a ceremonial parade. They had a band. They even had a girl who had been taught to imitate the antics of a peacetime Drum Major in the regular army. It is not, to my mind, the prettiest exercise in the world for the female body, but I must say she was doing it very well. You could see what endless pains and time had gone to her training. But at that moment my telephone rang.

It was a call from W. W. is a man who works very long hours in a most necessary profession. The scantiness of his leisure and the rarity of his enjoyments gives a certain sacrosanctity to all one’s engagements with him: that is why I have had an evening with him on the first Wednesday of every month for more years than I can remember. It is a law of the Medes and Persians. He had rung up to say that he wouldn’t be able to come this Wednesday. He is in the Home Guard, and his platoon were all being turned out that evening (all after their day’s work) to practise – ceremonial slow marching. “What about Friday?” I asked. No good; they were being paraded on Friday evening for compulsory attendance at a lecture on European affairs. “At least”, said I, “I’ll see you at church on Sunday evening.” Not a bit of it. His platoon – I happen to know that W. is the only Christian it contains – were being marched off to a different church, two miles away; a church to which W. has the strongest doctrinal objections. “But look here,” I asked in my exasperation, “what the blazes has all this tomfoolery got to do with the purposes for which you originally joined the old L.D.V.?” (Note: The Local Defence Volunteers were organized in May 1940 for men between the ages of 17 and 65. Their purpose was to deal with German parachutists. The name was changed to the Home Guard in December 1940, and conscription began in 1941.) W., however, had rung off.

The final blow fell that evening in Common Room. An influential person was present and I’m almost sure I heard him say, “Of course we shall retain some kind of conscription after the war; but it won’t necessarily have anything to do with the fighting services.” It was then that I stole away to bed and had my dream.

I dreamed that a number of us bought a ship and hired a crew and captain and went to sea. We called her the State. And a great storm arose and she began to make heavy weather of it, till at last there came a cry “All hands to the pumps – owners and all!” We had too much sense to disobey the call and in less time than it takes to write the words we had all turned out, and allowed ourselves to be formed into squads at the pumps. Several emergency petty officers were appointed to teach us our work and keep us at it. In my dream I did not, even at the outset, greatly care for the look of some of these gentry; but at such a moment – the ship being nearly under – who could attend to a trifle like that? And we worked day and night at the pumps and very hard work we found it. And by the mercy of God we kept her afloat and kept her head on to it, till presently the weather improved.

I don’t think that any of us expected the pumping squads to be dismissed there and then. We knew that the storm might not be really over and it was as well to be prepared for anything. We didn’t even grumble (or not much) when we found that parades were to be no fewer. What did break our hearts were the things the petty officers now began to do to us when they had us on parade. They taught us nothing about pumping or handling a rope or indeed anything that might help to save their lives or ours. Either there was nothing more to learn or the petty officers did not know it. They began to teach us all sorts of things – the history of shipbuilding, the habits of mermaids, how to dance the hornpipe and play the penny whistle and chew tobacco. For by this time the emergency petty officers (though the real crew laughed at them) had become so very, very nautical that they couldn’t open their mouths without saying “Shiver my timbers” or “Avast” or “Belay”.

And then one day, in my dream, one of them let the cat out of the bag. We heard him say, “Of course we shall keep all these compulsory squads in being for the next voyage: but they won’t necessarily have anything to do with working the pumps. For, of course, shiver my timbers, we know there’ll never be another storm, d’ you see? But having once got hold of these lubbers we’re not going to let them slip back again. Now ‘s our chance to make this the sort of ship we want.”

But the emergency petty officers were doomed to disappointment. For the owners (that was “us” in the dream, you understand) replied “What? Lose our freedom and not get security in return? Why, it was only for security we surrendered our freedom at all.” And then someone cried, “Land in sight”. And the owners with one accord took every one of the emergency petty officers by the scruff of his neck and the seat of his trousers and heaved the lot of them over the side. I protest that in my waking hours I would never have approved such an action. But the dreaming mind is regrettably immoral, and in the dream, when I saw all those meddling busybodies going plop-plop into the deep blue sea, I could do nothing but laugh.

My punishment was that the laughter woke me up.

Leave a Reply